Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Diiamb Foot

Diiamb is a metrical foot used in metered poetry. It consists of (four syllables) a short syllable, long syllable short syllable and a long syllable. Look at the diiamb as two iambs in qualitative meter measuring a single foot; thus representing an unstressed syllable, stressed syllable, unstressed syllable and a stressed syllable as shown in Table above.

In verses 1, 7, and 12 of the first stanza of the poem “Ode to Sweet Revenge - Ground Zero Never” shown below:

1 He is cleaning the House; they want it done with lightning speed

7 Forget the two wars with hidden goals that tanked their economy;

12 So here’s the beef feeding my head on a tropical island

When scanned shows where the Diiamb foot appears. Take a look.

Monday, November 21, 2011

Diacritical Marks for Tetrasyllables

Now there are quite a number of diacritical marks associated with Tetrasyllables and their corresponding foot types. These are summarized in the Table below:

Labels:

diacritical marks,

ionics,

tetrasyllable

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Rhyme Scheme for the National Anthem of the United Kingdom

God save our gracious Queen,

Long live our noble Queen,

God save the Queen!

Send her victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us,

God save the Queen!

O lord God arise,

Scatter our enemies,

And make them fall!

Confound their politics,

Frustrate their knavish tricks,

On you our hopes we fix,

God save the Queen!

Not in this land alone,

But be God's mercies known,

From shore to shore!

Lord make the nations see,

That men should brothers be,

And form one family,

The wide world ov'er

From every latent foe,

From the assasins blow,

God save the Queen!

O'er her thine arm extend,

For Britain's sake defend,

Our mother, prince, and friend,

God save the Queen!

Thy choicest gifts in store,

On her be pleased to pour,

Long may she reign!

May she defend our laws,

And ever give us cause,

To sing with heart and voice,

God save the Queen!

Lord grant that Marshal Wade,

May by thy mighty aid,

Victory bring,

May he sedition hush,

And like a torrent rush

Rebellious Scots to crush,

God save the Queen!

The rhyme scheme for the six septet stanzas for the National Anthem of the United Kingdom is as follows:

aAAbbbA xxxcccA ddefffe eeAgggA eexhhxA iixjjjA

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Rhyme Scheme for the National Anthem of the USA

The Star Spangled Banner

By Francis Scott Key 1814

Stanza 1 Rhyme Scheme

Oh, say can you see by the dawn's early light a

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming? b

Whose broad stripes and bright stars thru the perilous fight, a

O'er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming? b

And the rocket's red glare, the bombs bursting in air, c

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. c

Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave d

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave? d

Stanza 2

On the shore, dimly seen through the mists of the deep, e

Where the foe's haughty host in dread silence reposes, f

What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep, e

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses? f

Now it catches the gleam of the morning's first beam, g

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream: g

'Tis the star-spangled banner! Oh long may it wave D

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! D

Stanza 3

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore c

That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion, h

A home and a country should leave us no more! c

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution. h

No refuge could save the hireling and slave d

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave: d

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave D

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! D

Stanza 4

Oh! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand i

Between their loved home and the war's desolation! h

Blest with victory and peace, may the heav'n rescued land i

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation. h

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, j

And this be our motto: "In God is our trust." j

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave D

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! D

Someone on this blog asked: What is the rhyme scheme of "The Star Spangled Banner"? So here it is. The capital letters in the Rhyme Scheme indicate repeated rhymes.

ab ab cc dd ef ef gg DD ch ch dd DD ih ih jj DD

By Francis Scott Key 1814

Stanza 1 Rhyme Scheme

Oh, say can you see by the dawn's early light a

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming? b

Whose broad stripes and bright stars thru the perilous fight, a

O'er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming? b

And the rocket's red glare, the bombs bursting in air, c

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there. c

Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave d

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave? d

Stanza 2

On the shore, dimly seen through the mists of the deep, e

Where the foe's haughty host in dread silence reposes, f

What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep, e

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses? f

Now it catches the gleam of the morning's first beam, g

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream: g

'Tis the star-spangled banner! Oh long may it wave D

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! D

Stanza 3

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore c

That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion, h

A home and a country should leave us no more! c

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution. h

No refuge could save the hireling and slave d

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave: d

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave D

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! D

Stanza 4

Oh! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand i

Between their loved home and the war's desolation! h

Blest with victory and peace, may the heav'n rescued land i

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation. h

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, j

And this be our motto: "In God is our trust." j

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave D

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave! D

Someone on this blog asked: What is the rhyme scheme of "The Star Spangled Banner"? So here it is. The capital letters in the Rhyme Scheme indicate repeated rhymes.

ab ab cc dd ef ef gg DD ch ch dd DD ih ih jj DD

Monday, September 26, 2011

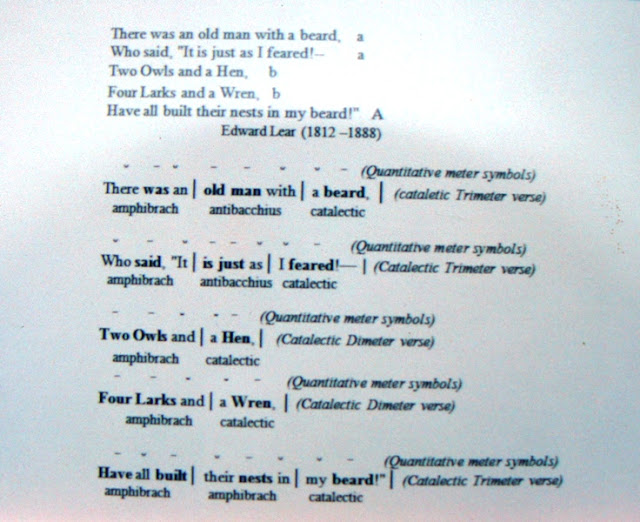

The Amphibrach Foot

Amphibrach

The trisyllabic metrical foot is made up of three syllables that can either be stressed or unstressed respectively as in accentual-syllabic meter or long or short as in quantitative meter. The Amphibrach is trisyllabic because it has three syllables and is identified has having its stressed syllable surrounded by two unstressed syllables as shown in the Table below:

The amphibrach is the main foot used in the writing classical limerick poems. The poems below are used as examples.

The scansion of the Limerick written by Edward Lear (1812 –1888) in quantitative meter is shown where the amphibrach foot in the poem with trimeter (3) and dimeter (2) verses in a rhyme scheme aabbA is used. The capital letter in the rhyme scheme indicates a repeated rhyme in the last verse.

The scansion on this Limerick of unknown origin shown below makes use of the amphibrach foot with tetrameter (4) and dimeter (2) verses in a rhyme scheme aabba; the raised numbers in the rhyme scheme indicate foot pattern of the verses.

What is meant by catalectic? When a verse is a metrically incomplete that is, lacking a syllable at the end or ending with an incomplete foot, such a verse is referred to as being catalectic.

Shown below is the scansion on the Limerick by a 21st Century poet. It is made up of the amphibrach exclusively. The rhyme scheme sits on aabba. The first, second and fifth verses are in Trimeter. The third and fourth verses are in Dimeter. Take a look:

The amphibrach is the main foot used in the writing classical limerick poems. The Limerick is a kind of a witty, humorous, or nonsense poem, especially one in five verse amphibrachic meter or anapestic with strict rhyme scheme aabba. The form can be found in England as of the early years of the 18th century. It was popularized by Edward Lear in the 19th century, although he never used the term limerick.

Diacritical Marks for Disyllable Foot Types

You should be aware by now that the poetic foot is classified by the number of syllables in the word. The Disyllable Foot Types are made of specific diacritical marks for each type of foot and diacritical marks in terms of vowel length in quantitative meter as well as the accentual-syllabic meter in English language poetry. The Table below summaries all the diacritical marks associated with the disyllable foot covered in previous blogs.

Just click on each of the following diacritical marks below table to review the blog entry on it, if you so desire.

̷ ̷ spondee

ᵕ ᵕ pyrrhic

̷ ᵕ trochee

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

The Amphibrach Foot

The trisyllabic metrical foot is made up of three syllables that can be stressed or unstressed as in accentual-syllabic meter or can either be long or short as in quantitative meter. The Amphibrach is trisyllabic because it has three syllables and is identified has having its stressed syllable surrounded by two unstressed syllables as shown in the Table 6.

Here is a scan of the 1st Stanza of the poem “Ode to Poetry” with quantitative meter symbols showing the use of the amphibrach.

Since poetry is the food of the senses

Cart me heaps of heavy loads of wholesome flesh,

Beneath the skin and on the bone;

Like a flamingo, I take my time to pick,

And eat with delightful intensity,

Savory cuts of great poetry.

Scansion of Edward Lear’s poem “Calico Pie” shows his skillful use of the amphibrach. Take a look.

Calico Pie,

The little Birds fly

Down to the calico tree,

Their wings were blue,

And they sang “Tilly-loo!”

Till away they flew,

And they never came back to me!

They never came back!

They never came back!

They never came back to me!

This pattern is rightly credited the funny poetry of Edward Lear who wrote such for his patron’s grand children in 1840. However, many variations to this pattern have persisted and continue to do so throughout the ages. Nevertheless, all have drawn inspiration from the classical limerick mode of Edward Lear’s funny poetry. It can truly be said that Edward Lear was a precursor to Limerick poetry, although he never used the term limerick. Here is scansion of one of his funny poems in quantitative meter showing his effective use of the amphibrach foot in “There was a young lady whose chin” as shown below:

There was a young lady whose chin, a

Resembled the point of a pin; a

So she had it made sharp, b

And purchased a harp, b

And played several tunes with her chin. A

Here is a scan of the 1st Stanza of the poem “Ode to Poetry” with quantitative meter symbols showing the use of the amphibrach.

Since poetry is the food of the senses

Cart me heaps of heavy loads of wholesome flesh,

Beneath the skin and on the bone;

Like a flamingo, I take my time to pick,

And eat with delightful intensity,

Savory cuts of great poetry.

Calico Pie,

The little Birds fly

Down to the calico tree,

Their wings were blue,

And they sang “Tilly-loo!”

Till away they flew,

And they never came back to me!

They never came back!

They never came back!

They never came back to me!

The basic metron of classical limerick poems is the amphibrach, and the traditional limerick pattern that has somewhat emerged is shown in Table 7.

This pattern is rightly credited the funny poetry of Edward Lear who wrote such for his patron’s grand children in 1840. However, many variations to this pattern have persisted and continue to do so throughout the ages. Nevertheless, all have drawn inspiration from the classical limerick mode of Edward Lear’s funny poetry. It can truly be said that Edward Lear was a precursor to Limerick poetry, although he never used the term limerick. Here is scansion of one of his funny poems in quantitative meter showing his effective use of the amphibrach foot in “There was a young lady whose chin” as shown below:

There was a young lady whose chin, a

Resembled the point of a pin; a

So she had it made sharp, b

And purchased a harp, b

And played several tunes with her chin. A

Here is a scan of a Limerick "Wiener Souse" with quantitative meter symbols by a 21st Century poet showing all the five verses making use of the amphibrach only and rhyming aabba.

Labels:

amphibrach foot,

Edward Lear,

funny poems,

limerick

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Foot in Bacchius

A trisyllable foot consisting of a short vowel followed by two long vowels in quantitative meter or an unstressed syllable followed by two stressed syllables in qualitative meter found in English verse is called the Bacchius as shown in the table below.

It is a rare metrical foot found in poetry but here are examples of its use found

in this poem:

Keats “Ode to a Nightingale” Stanza 1, verses 1-6 as scanned below:

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness, -

It is a rare metrical foot found in poetry but here are examples of its use found

in this poem:

Keats “Ode to a Nightingale” Stanza 1, verses 1-6 as scanned below:

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness, -

Saturday, September 3, 2011

Antibacchius Foot

Antibacchius is a foot of three syllables in quantitative meter consisting of two long syllables followed by short syllable. In qualitative meter it is shown as two stressed syllables followed by an unstressed syllable as shown below.

Example of the use of this Antibacchius is shown below in the scansion of the first seven verses of the first stanza of the “Ode to Black Pudding and Souse”. Those verses containing the Antibacchius foot are italicized. Take a look.

Small chattel-house where she was born and raised

In Maycock's village, her ancestral home;

Bare-footed youth on Sunday evenings did walk

Rope leashed black-belly sheep and goats to graze

Weeds and grass on dust roads with out sidewalk;

Mindful of cane-fields that grow planters' cash,

As arrowed canes swayed in breeze before cropping bash;

Look what happens when this same first stanza of the “Ode to Black Pudding and Souse” is rescanned and the Antibacchius foot in quantitative meter is replaced for some other foot type using qualitative meter. Compare and contrast the first and second scansion of the stanza and draw your own conclusions.

Small chattel-house where she was born and raised

In Maycock's village, her ancestral home;

Bare-footed youth on Sunday evenings did walk

Rope leashed black-belly sheep and goats to graze

Weeds and grass on dust roads with out sidewalk;

Mindful of cane-fields that grow planters' cash,

As arrowed canes swayed in breeze before cropping bash;

Example of the use of this Antibacchius is shown below in the scansion of the first seven verses of the first stanza of the “Ode to Black Pudding and Souse”. Those verses containing the Antibacchius foot are italicized. Take a look.

Small chattel-house where she was born and raised

In Maycock's village, her ancestral home;

Bare-footed youth on Sunday evenings did walk

Rope leashed black-belly sheep and goats to graze

Weeds and grass on dust roads with out sidewalk;

Mindful of cane-fields that grow planters' cash,

As arrowed canes swayed in breeze before cropping bash;

Small chattel-house where she was born and raised

In Maycock's village, her ancestral home;

Bare-footed youth on Sunday evenings did walk

Rope leashed black-belly sheep and goats to graze

Weeds and grass on dust roads with out sidewalk;

Mindful of cane-fields that grow planters' cash,

As arrowed canes swayed in breeze before cropping bash;

Thursday, September 1, 2011

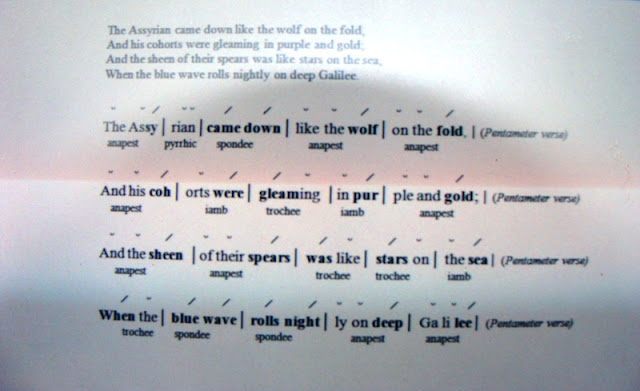

Foot in Anapest

The Anapest fits snuggly as a trisyllabic metrical foot made up of three syllables obviously. The British spelling for it is Anapaest and the American spelling is Anapest. This anapestic foot is shown in the Table above and is made up of two short syllables followed by one long syllable in quantitative meter; and in accentual-syllabic meter used in English language poetry two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable . By the way “meter” is American spelling and the British spelling is “metre”. The Anapest is also known as the Antidactylus because the dactyl ( ̷ ᵕ ᵕ ) has this symbolic pattern in reversed order.

English language poetry tends to use the Anapest as the dominant foot in the writing of Limericks. In accentual-syllabic meter the Anapest because it ends with a stressed syllable easily facilitates strong end-rhymes and tends to create a very rolling, galloping feeling verse, and allows for long verses with a great deal of internal complexity. The poem used as an example is “The Destruction of Sennacherib” by the poet Lord George Gordon Bryon published in 1815. This poem describes the events that are chronicled in 2 Kings 18-19 of the Bible.

The stanzas from Bryon’s poem are scanned to show the effects of the anapest in Qualitative meter giving rise to Pentameter verses. Take a look.

Shown below is the scansion on the Limerick by a 21st Century poet where the anapest is a key component of the verses. The rhyme scheme is aabba. The first, second and fifth verses are in Tetrameter. The third and fourth verses are in Trimeter. Take a look:

But some Anapestic Limericks have this rhyme scheme aabca, shown below.

The poet Lewis Carroll is famous for his masterful use of the Anapest in Tetrameter verses rhyming abab. Here is an example of a stanza taken from his poem, “The Hunting of the Snark”. In the example the anapest is underlined for quick recognition.

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Diacritical Marks for Trisyllables

Now there are quite a number of diacritical marks associated with Trisyllables and their corresponding foot types. These are summarized in the Table below:

Just click on each of the following diacritical marks to review the blog entry on it, if you so desire.

Amphibrach ᵕ ̵ ᵕ

Anapest or Antidactylus ᵕ ᵕ ̷

Antibacchius ̵ ̵ ᵕ

Baccius ᵕ ̵ ̵

Cretic or Amphimacer ̵ ᵕ ̵

Dactyl ̷ ᵕ ᵕ

Molossus ̵ ̵ ̵̵̵̵̵

Tribrach ᵕ ᵕ ᵕ

Just click on each of the following diacritical marks to review the blog entry on it, if you so desire.

Amphibrach ᵕ ̵ ᵕ

Anapest or Antidactylus ᵕ ᵕ ̷

Antibacchius ̵ ̵ ᵕ

Baccius ᵕ ̵ ̵

Cretic or Amphimacer ̵ ᵕ ̵

Dactyl ̷ ᵕ ᵕ

Molossus ̵ ̵ ̵̵̵̵̵

Tribrach ᵕ ᵕ ᵕ

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Pyrrhic the Mirror Image of Dibrach

The Pyrrhic Foot

In the Table below notice how two short vowels” of the Quantitative Meter equate with two unstressed syllables of Accentual-Syllabic forms in Qualitative meter. These iconic symbols represent the Pyrrhic foot.

These two short vowel symbols (ᵕ ᵕ) are known as the dibrach in quantitative meter of the Greek and Roman poetry. In English poetry where qualitative meter is used, these two short syllable symbols ( ᵕ ᵕ) are known as a pyrrhic. The pyrrhic is not used to construct an entire poem due to its monotonous sound effect.

In Verses 1, 2, 3 and 4 of stanza 50 of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam”, measuring four iambic tetrameter verses rhyming abba, in the sequence of lyrics make in memoriam an “envelope stanza” to his friend Arthur Henry Hallam in 1849 shows the use of the pyrrhic. In this excerpt one cannot but notice that he used the pyrrhic foot only two times in the stanza used here as an exemplar. Take a look:

Envelope Stanza is a quatrain with the rhyme scheme abba, such that verses 2 and 3 are enclosed between the rhymes of verses 1 and 4.

In the Table below notice how two short vowels” of the Quantitative Meter equate with two unstressed syllables of Accentual-Syllabic forms in Qualitative meter. These iconic symbols represent the Pyrrhic foot.

These two short vowel symbols (ᵕ ᵕ) are known as the dibrach in quantitative meter of the Greek and Roman poetry. In English poetry where qualitative meter is used, these two short syllable symbols ( ᵕ ᵕ) are known as a pyrrhic. The pyrrhic is not used to construct an entire poem due to its monotonous sound effect.

In Verses 1, 2, 3 and 4 of stanza 50 of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam”, measuring four iambic tetrameter verses rhyming abba, in the sequence of lyrics make in memoriam an “envelope stanza” to his friend Arthur Henry Hallam in 1849 shows the use of the pyrrhic. In this excerpt one cannot but notice that he used the pyrrhic foot only two times in the stanza used here as an exemplar. Take a look:

Envelope Stanza is a quatrain with the rhyme scheme abba, such that verses 2 and 3 are enclosed between the rhymes of verses 1 and 4.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

A Foot to Spondee and crossing over to Trochee

The Spondee

In Table below notice how the “long vowels” of the Quantitative Meter equate with the “stressed syllables of Accentual-Syllabic forms in Qualitative meter with respect to the Spondee. The Spondee still measures a foot even though it has one sound that is stressed.

Being edited will be right back soon

In Verses 1, 2, and 3 of stanza 50 taken from the poem “In Memoriam”, by Alfred Lord Tennyson are examples of the use of the Spondee as shown below:

The Trochee

In the Table below notice how the “long and short vowels” of the Quantitative Meter equate with the “stressed and unstressed syllables of Accentual-Syllabic forms in Qualitative meter with respect to the Trochee.

Trochee is called a falling meter because its sound falls from stressed to unstressed. In Verses 1, 2, 3 and 4 of stanza 50 of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” show how the trochee is used or not used with other metrical foot types. Take a look:

Have you noticed that in quatrain 50 Verse 2 of “In Memoriam” only has a trochee and is not used anywhere else in the quatrain rhyming abba. As you read the verses aloud do you not feel that this verse has dramatically shifted the tempo away from the tempo established in the other three verses in the quatrain? Well that is what happens when the poet decides not to use verses made up entirely of iambs but pepper the iambs with other foot types. Also, Verse 2 is a Tetrameter Verse while the other three verses are Iambic Tetrameters. There are no iambs in Verse 2 but still measures four feet; hence the reason why it is simply called a Tetrameter Verse.

A quatrain is a stanza, or a complete poem, consisting of four verses with a defined rhyme scheme. The significance of the quatrain lies in the fact that it can easily be memorized because it contains only four verses.

In Table below notice how the “long vowels” of the Quantitative Meter equate with the “stressed syllables of Accentual-Syllabic forms in Qualitative meter with respect to the Spondee. The Spondee still measures a foot even though it has one sound that is stressed.

In Verses 1, 2, and 3 of stanza 50 taken from the poem “In Memoriam”, by Alfred Lord Tennyson are examples of the use of the Spondee as shown below:

The Trochee

In the Table below notice how the “long and short vowels” of the Quantitative Meter equate with the “stressed and unstressed syllables of Accentual-Syllabic forms in Qualitative meter with respect to the Trochee.

Trochee is called a falling meter because its sound falls from stressed to unstressed. In Verses 1, 2, 3 and 4 of stanza 50 of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” show how the trochee is used or not used with other metrical foot types. Take a look:

Have you noticed that in quatrain 50 Verse 2 of “In Memoriam” only has a trochee and is not used anywhere else in the quatrain rhyming abba. As you read the verses aloud do you not feel that this verse has dramatically shifted the tempo away from the tempo established in the other three verses in the quatrain? Well that is what happens when the poet decides not to use verses made up entirely of iambs but pepper the iambs with other foot types. Also, Verse 2 is a Tetrameter Verse while the other three verses are Iambic Tetrameters. There are no iambs in Verse 2 but still measures four feet; hence the reason why it is simply called a Tetrameter Verse.

A quatrain is a stanza, or a complete poem, consisting of four verses with a defined rhyme scheme. The significance of the quatrain lies in the fact that it can easily be memorized because it contains only four verses.

Saturday, August 20, 2011

The Foot of Iamb

In Table above notice how the symbols for “long and short vowels” in disyllable of the Quantitative Meter equate with the “stressed and unstressed disyllable of Accentual-Syllabic forms in Qualitative meter with respect to the Iamb, the most common metrical foot in English and other languages as well.

The Iamb is called a rising meter because its sound rises from unstressed sound to a stressed sound. The four verses in Stanza 50 of Lord Tennyson’s poem "In Memoriam" provide examples of iambs used in English poetry.

In Memoriam

Stanza 50

1 Be near me when my light is low,

2 When the blood creeps, and the nerves prick

3 And tingle; and the heart is sick,

4 And all the wheels of Being slow.

And show the results from the four verses scanned as follows:

The scansion of these four verses has provided some basic clues as to the structure and form of the verses in the poem. Verses 1 and 3 of stanza 50 make use of the iamb and other foot types but still measures four feet each in Non-Standard Iambic Tetrameter verse. Verse 2 has no iambs but still measures four feet; without any iambs present it cannot be called an Iambic Tetrameter verse, but simply a Tetrameter Verse. Verse 4 is made up entirely of iambs and measures four iambic feet and is rightly called a Standard Iambic Tetrameter verse. The iamb is clearly recognized for its monotonous rhythmic tone (da-dum, da-dum, da-dum); probably the reason why Lord Tennyson mixed iambs with other foot types like the spondee, pyrrhic to shake up the rhythmic flow.

A Standard iambic verse regardless of the length of the foot is a verse containing all its feet made up of iambs.

A Non-standard iambic verse regardless of the length of the foot has the iambs mixed with other foot types for example the, trochee, spondee, dactyl, anapest and pyrrhic. This structure counteracts the metronomic effect by substituting for an iamb another type of foot whose stress is different. The first foot in the verse is the one most likely to change. The second foot is almost always an iamb. This is where the “inversion technique” is used. This technique allows iambic tetrameter verses (and other types of iambic feet, example iambic pentameter) to retain their dominance in spite of being invaded by other foot types. The inversion technique imposes strict compliance in that there must be no compromising on the required length of feet; so an iambic tetrameter must measure four feet, the iambic pentameter must measure five feet, iambic hexameter must measure six feet and so on. Most inversions tend to fall on the trochee.

In the poetic world, no one goes around saying Non-standard and Standard Iambic Tetrameter as the case may be; so long as the verses measure four feet the qualifier is not needed, just simply Iambic Tetrameter, Iambic Pentameter, whatever the case may be is the acceptable term used in poetry analysis.

Attention must be drawn to the fact that in addition to having poems written in classical Hexameter, over centuries English poems have shifted from classical Hexameter to Iambic Hexameter. An example of this shifting is seen in poems written by Michael Drayton and other eminent poets through the ages. Drayton used iambic hexameter couplets way back in 1612 in his “Poly-Olbion”. Here is an example from his works:

Classical English poets have experienced great difficulty in writing poems with Dactylic Hexameter verses. The position taken on this is that English leaves vowels and consonants out from words, thus becoming a problem because the Hexameter relies on phonetics, and sounds always have fixed positions. Several attempts were made in the 18th century to adapt Dactylic Hexameter into English Iambic Pentameter. An example of this is found “Couplets on Wit” by Alexander Pope where he used Heroic Couplets (a pair of rhyming verses written in iambic pentameter) an example is shown in Stanza VI taken from the poem where he use quite effectively iambs in the creation of Iambic Pentameter verses in heroic couplets; and disregarded the use of the Dactylic Hexameter. The Dactylic Hexameter has never been popularly used in English, where the standard meter is iambic pentameter. Take a look:

Couplets on Wit (Stanza VI)

Wou’d you your writings to some Palates fit

Purged all you verses from the sin of wit

For authors now are conceited grown

They praise no works but what are like their own

Have you noticed that in verse 3 of the exampler that the last foot is incomplete, that is, there is a syllable missing? In poetry this is exceptable. What the poet has done is to shift the feeling of the poem, a technique so often used to achieve a certain effect. So in addition to this verse being an iambic pentameter, it is also a catalectic verse in iambic pentameter. A safe definition for this type of verse probably would go like this: A catalectic verse is a metrically incomplete verse, lacking a syllable at the end or ending with an incomplete foot.

Heroic Couplet

A pair of rhyming verses written in Iambic Pentameter is termed a Heroic couplet. It was so called for its use in the composition of epic poetry in the 17th and 18th centuries. The couplet is formed with the use of two successive verses of poetry with equal length and rhythmic correspondence with end words that rhyme.

Geoffrey Chaucer created the “heroic couplet” easily recognized in his “Canterbury Tales”. A couplet for special purposes, is the shortest stanza form, but is frequently joined with other couplets to form a poem with stanzas of four verses with each verse having ten-syllables. So it is easy to figure out why the “heroic couplet” bears such names as the decasyllabic quatrain also known as the “heroic stanza”, or “heroic quatrain”. Thus, the decasyllabic quatrain consists of four verses with a rhyme scheme of aabb or abab.

Note however, that “heroic couplets are also formed with no stanza divisions, as in Roberts Browning’s “My Last Duchess”. See excerpt of poem scanned below:

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Dactylic Hexameter

Dactyl is a foot in metered poetry having the first syllable long followed by two short syllables in quantitative meter shown by the following symbols ̵ ᵕ ᵕ and in qualitative meter the dactyl has a pattern where the first syllable is stressed followed by two unstressed syllables shown by this pattern ̷ ᵕ ᵕ so the word “poetry” ( p̅o ět řy ) is itself a dactyl and measures one foot.

Click here to read all verses in Spider in the Web

The dactyl is what defines the Hexameter. The Hexameter consists of six feet. It is also called the “Dactylic Hexameter” and the “Heroic Hexameter”. It has traditionally been associated with the Quantitative meter of classical epic poetry in both Greek and Latin. The poets of that era considered the Hexameter to be the grand style of classical poetry of which Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid are the premier examples. The dactyl ( ̷ ᵕ ᵕ ) a long syllable and two short syllables is what drives the Hexameter foot but it allows for the inclusion of two long syllables ( ̷ ̷ ) called a spondee. A short syllable ( ᵕ ) is a syllable with a short vowel and one consonant at the end (example: ăt but it is long in ātlas). A long syllable ( ̷ ) is a syllable that either has a long vowel, two or more consonants at the end; a long consonant or both (example: latch key). Space between words doesn’t matter.

The following chart below shows the variable patterns which are acceptable when writing classical Hexameter verses:

Specifically though, the first four feet can be dactyls or spondees, more or less freely. The fifth foot must be a dactyl. The sixth foot is always a spondee, though it may be an anceps syllable. Homer’s hexameters contain a far higher proportion of dactyls than later hexameter poetry. Homer used dialectal form that is, altering the forms of words so that words fitted the hexameter.

Below is an excerpt from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem "Evangeline" Preface: A Tale of Acadie shows the classical Dactylic Hexameter foot patterns.

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines, and the hemlocks,Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman

Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian farmers,-

The dactyl appears in the compulsory fifth foot and the spondee in the compulsory sixth foot, this final metron is represented by ( ̵ x ) but in any given Dactylic Hexameter verse it is not uncommon to find either a trochee ( ̵ ᵕ ) or a spondee ( ̵ ̵ ) but what happens when the Dactylic Hexameter has a trochee in the last foot when the rules of the Dactylic Hexameter insist that the anceps in the last foot must be a spondee; poetic license allows for the anceps x to be changed into a long syllable through the process known as poetic license, thus during the scansion of the poem the trochee becomes a spondee automatically. The anceps is a “free syllable” or “variable syllable” in a verse of poetry. The syllable may be either long or short or "irrational" depending on the meter being discussed. In Quantitative meter the symbol “x” is used when anceps occur.

In the following excerpt from the poem, “The Invader” Stanza I is written in Dactylic Hexameter using qualitative meter by a 21st century poet. Take a look at what its scansion revealed:

The Invader

Stanza 1

Soon as the girl in her night gown closed door, climbed on the bedspread;

Clinging to window, a bug in a web cage; spider on soft lace;

Looking from skyline tall poles, stuck deep, lighting the homestead,

Hot air blowing in! Spider in bedroom, crawling in Jane's space.

The five verses from“Aeneid” by the Roman poet Virgil show a full scansion.

Notice that in the scansion of the Dactylic Hexameter poem above, three vertical symbols (│ ⁞ ║) stand serving a very specific function in the scansion process. Scansion is the analysis of metrical patterns seen in verses of a poem written in closed form. Closed form or metered poetry is characterized by regular and consistency in such elements as rhyme, verse length, and metrical pattern.

This symbol │is called the Diaeresis. The diaeresis marks the boundary between the end of a foot and the beginning of the next foot. The diaeresis never occurs within a foot and does not mark any discernible pause in the sense of the poem.

This symbol║ the “double pipe” is called the Caesura. Typically the caesura is significant when it occurs near the middle of the verse and correlates with a break of sense in the verse, such as a punctuation mark. The caesura divides the verse and allows the poet to vary the basic metrical pattern being worked on. There are two types of caesura: masculine and feminine. A masculine caesura is a pause that follows a stress syllable; a feminine caesura follows an unstressed syllable.

Another characteristic of the caesura is the position it holds in the verse. A pause close to the beginning of a verse is called an initial caesura, at the middle of the verse it’s called a medial caesura, and near the end of the verse it's called a terminal caesura.

Caesurae are popular in Greek and Latin versification, especially in heroic verse form, the Dactylic Hexameter. Versification is the process of turning prose into verse using versifier tools such as content, form, poetic diction, measurement, sound effects and elements of poetry. In theory a caesura may occur in any of the six feet, and in fact most verses have two or more caesurae. The principal caesura marks the most obvious pause in the sense, and is usually in the third foot (although it often appears in the second and fourth feet as well).

This symbol ⁞ is called the Bucolic Diaeresis. The bucolic diaeresis is a common feature in the scansion of dactylic hexameter where it is placed between the fourth and fifth feet of a verse and must end with the rhythm of dum-di-di dum-dum. This word, “bucolic” comes from the Greek word boukolos, “herdsman” because dactylic poetry of the herdsmen was notorious for “shave and a haircut” verse ending.

The Roman poet Ennius introduced the Elegiac Couplet to Latin poetry for themes less lofty than that of epic, for which dactylic hexameter was suited. An Elegiac Couplet is a pair of sequential verses in poetry in which the first verse is written in dactylic hexameter and the second verse in dactylic pentameter.

Ovid, the ancient Roman poet is considered the master of the elegiac couplet and in his “Amores” provides striking examples of this. The first two verses of his “Amores” shown below are scanned to show how he structured his elegiac couplets without end rhymes. End rhymes are never a common feature in Roman elegiac couplets.

The dactyl is what defines the Hexameter. The Hexameter consists of six feet. It is also called the “Dactylic Hexameter” and the “Heroic Hexameter”. It has traditionally been associated with the Quantitative meter of classical epic poetry in both Greek and Latin. The poets of that era considered the Hexameter to be the grand style of classical poetry of which Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid are the premier examples. The dactyl ( ̷ ᵕ ᵕ ) a long syllable and two short syllables is what drives the Hexameter foot but it allows for the inclusion of two long syllables ( ̷ ̷ ) called a spondee. A short syllable ( ᵕ ) is a syllable with a short vowel and one consonant at the end (example: ăt but it is long in ātlas). A long syllable ( ̷ ) is a syllable that either has a long vowel, two or more consonants at the end; a long consonant or both (example: latch key). Space between words doesn’t matter.

The following chart below shows the variable patterns which are acceptable when writing classical Hexameter verses:

Specifically though, the first four feet can be dactyls or spondees, more or less freely. The fifth foot must be a dactyl. The sixth foot is always a spondee, though it may be an anceps syllable. Homer’s hexameters contain a far higher proportion of dactyls than later hexameter poetry. Homer used dialectal form that is, altering the forms of words so that words fitted the hexameter.

Below is an excerpt from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem "Evangeline" Preface: A Tale of Acadie shows the classical Dactylic Hexameter foot patterns.

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines, and the hemlocks,Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman

Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian farmers,-

The dactyl appears in the compulsory fifth foot and the spondee in the compulsory sixth foot, this final metron is represented by ( ̵ x ) but in any given Dactylic Hexameter verse it is not uncommon to find either a trochee ( ̵ ᵕ ) or a spondee ( ̵ ̵ ) but what happens when the Dactylic Hexameter has a trochee in the last foot when the rules of the Dactylic Hexameter insist that the anceps in the last foot must be a spondee; poetic license allows for the anceps x to be changed into a long syllable through the process known as poetic license, thus during the scansion of the poem the trochee becomes a spondee automatically. The anceps is a “free syllable” or “variable syllable” in a verse of poetry. The syllable may be either long or short or "irrational" depending on the meter being discussed. In Quantitative meter the symbol “x” is used when anceps occur.

In the following excerpt from the poem, “The Invader” Stanza I is written in Dactylic Hexameter using qualitative meter by a 21st century poet. Take a look at what its scansion revealed:

The Invader

Stanza 1

Soon as the girl in her night gown closed door, climbed on the bedspread;

Clinging to window, a bug in a web cage; spider on soft lace;

Looking from skyline tall poles, stuck deep, lighting the homestead,

Hot air blowing in! Spider in bedroom, crawling in Jane's space.

The five verses from“Aeneid” by the Roman poet Virgil show a full scansion.

Notice that in the scansion of the Dactylic Hexameter poem above, three vertical symbols (│ ⁞ ║) stand serving a very specific function in the scansion process. Scansion is the analysis of metrical patterns seen in verses of a poem written in closed form. Closed form or metered poetry is characterized by regular and consistency in such elements as rhyme, verse length, and metrical pattern.

This symbol │is called the Diaeresis. The diaeresis marks the boundary between the end of a foot and the beginning of the next foot. The diaeresis never occurs within a foot and does not mark any discernible pause in the sense of the poem.

This symbol║ the “double pipe” is called the Caesura. Typically the caesura is significant when it occurs near the middle of the verse and correlates with a break of sense in the verse, such as a punctuation mark. The caesura divides the verse and allows the poet to vary the basic metrical pattern being worked on. There are two types of caesura: masculine and feminine. A masculine caesura is a pause that follows a stress syllable; a feminine caesura follows an unstressed syllable.

Another characteristic of the caesura is the position it holds in the verse. A pause close to the beginning of a verse is called an initial caesura, at the middle of the verse it’s called a medial caesura, and near the end of the verse it's called a terminal caesura.

Caesurae are popular in Greek and Latin versification, especially in heroic verse form, the Dactylic Hexameter. Versification is the process of turning prose into verse using versifier tools such as content, form, poetic diction, measurement, sound effects and elements of poetry. In theory a caesura may occur in any of the six feet, and in fact most verses have two or more caesurae. The principal caesura marks the most obvious pause in the sense, and is usually in the third foot (although it often appears in the second and fourth feet as well).

This symbol ⁞ is called the Bucolic Diaeresis. The bucolic diaeresis is a common feature in the scansion of dactylic hexameter where it is placed between the fourth and fifth feet of a verse and must end with the rhythm of dum-di-di dum-dum. This word, “bucolic” comes from the Greek word boukolos, “herdsman” because dactylic poetry of the herdsmen was notorious for “shave and a haircut” verse ending.

The dactyl ( ̵ ᵕ ᵕ ) is the metrical foot of Greek elegiac poetry. This verse form became a common poetic vehicle for conveying any strong emotion. A typical verse structure of an elegiac couplet is shown in the chart below.

The Roman poet Ennius introduced the Elegiac Couplet to Latin poetry for themes less lofty than that of epic, for which dactylic hexameter was suited. An Elegiac Couplet is a pair of sequential verses in poetry in which the first verse is written in dactylic hexameter and the second verse in dactylic pentameter.

Ovid, the ancient Roman poet is considered the master of the elegiac couplet and in his “Amores” provides striking examples of this. The first two verses of his “Amores” shown below are scanned to show how he structured his elegiac couplets without end rhymes. End rhymes are never a common feature in Roman elegiac couplets.

"Elegy for Angela Barnes, RN” is an elegiac couplet. Stanza 5 of the poem is scanned using quantitative meter symbols as an example to show the verses structured along the pattern of the classical elegiac couplets. In quantitative meter the symbol for the short syllable is the ᵕ and this symbol ̵ is used for the long syllable. The symbols used when scanning verses in qualitative meter show unstressed syllable as this ᵕ and the ̷ for stressed syllable. This is okay because the English unstressed syllable ᵕ is equivalent to the classical short syllable ᵕ and the English stressed syllable ̷ is equivalent to ̵ the symbol used for the classical long syllable.

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Foot in Cretic

Cretic is a metrical foot consisting of three syllables, the first long, the second short and the third long ( ̵ ᵕ ̵ ) also called amphimacer. It is most unusual to see verses in a poem made up exclusively with cretic verses. However, any verse mixing iambs and trochees could employ a cretic foot as a transition. In other words, a verse might have two iambs and two trochees, with a cretic foot between. These three verses taken from the homostrophic ode, “Midsummer’s Day Exquisiteness” and scanned in qualitative meter provide examples of the cretic foot.

The Homostrophic Ode consists of a number of stanzas alike in structure and rhyme scheme. The poet is free to choose in accordance with the demands of the contents:-

the form which the basic structure should take

the number of verses

verse length

rhyme scheme

An ode is typically a lyrical verse written in praise of, or dedicated to someone or something which captures the poet's interest or serves as an inspiration for the ode.

Every so often, in the scansion of a verse there appears at the end of the verse a foot that is missing, a syllable making the verse incomplete. This creates what is known as a catalectic ending. Catalectic is a metrically incomplete verse lacking a syllable at the end or ending with an incomplete foot.

The Homostrophic Ode consists of a number of stanzas alike in structure and rhyme scheme. The poet is free to choose in accordance with the demands of the contents:-

the form which the basic structure should take

the number of verses

verse length

rhyme scheme

An ode is typically a lyrical verse written in praise of, or dedicated to someone or something which captures the poet's interest or serves as an inspiration for the ode.

Every so often, in the scansion of a verse there appears at the end of the verse a foot that is missing, a syllable making the verse incomplete. This creates what is known as a catalectic ending. Catalectic is a metrically incomplete verse lacking a syllable at the end or ending with an incomplete foot.

Labels:

amphimacer,

catalectic,

cretic foot,

homostrophic ode

Monday, August 8, 2011

Why Grievous Valentine's Day is a Pseudo-elegiac couplet

The poem “Grievous Valentine’s Day” is described as a pseudo-elegiac couplet. Why is that? The last stanza of this poem is scanned in qualitative meter to find answers to the question as to why it is a fake elegiac couplet, and fake elegiac stanza even though it adheres to the concept of what an elegy should reflect.

What is an elegy? The elegy is a type of poem that shows lament, praise and consolation in a formal and sustained way over the death of a particular person. It should not be considered as a eulogy because a eulogy is prose written in praise of the character or achievements of a deceased person.

Here are some reasons why “Grievous Valentine’s Day” is a pseudo-elegiac couplet:

* The second verse of the poem is written in iambic pentameter instead of the compulsory iambic hexameter. This pattern prevails throughout the entire poem.

* The stanza is not made up of elegiac couplets. An elegiac couplet is a pair of sequential verses usually of equal length and rhythmic correspondence with end words that rhyme aabb. The first verse of the couplet is written in dactylic hexameter and second verse in iambic pentameter and the rhyme scheme abab.

* The stanza cannot be called an elegiac stanza. An elegiac stanza, in poetry, is made up of a quatrain in iambic pentameter with alternate verses rhyming. The stanzas in this poem do not conform to this specified format.

What is an elegy? The elegy is a type of poem that shows lament, praise and consolation in a formal and sustained way over the death of a particular person. It should not be considered as a eulogy because a eulogy is prose written in praise of the character or achievements of a deceased person.

Here are some reasons why “Grievous Valentine’s Day” is a pseudo-elegiac couplet:

* The second verse of the poem is written in iambic pentameter instead of the compulsory iambic hexameter. This pattern prevails throughout the entire poem.

* The stanza is not made up of elegiac couplets. An elegiac couplet is a pair of sequential verses usually of equal length and rhythmic correspondence with end words that rhyme aabb. The first verse of the couplet is written in dactylic hexameter and second verse in iambic pentameter and the rhyme scheme abab.

* The stanza cannot be called an elegiac stanza. An elegiac stanza, in poetry, is made up of a quatrain in iambic pentameter with alternate verses rhyming. The stanzas in this poem do not conform to this specified format.

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Antipast Foot

Antipast is a metrical foot used in metered poetry. It consists of a short syllable, two long syllables and a short syllable ˘ ¯ ¯ ˘. English poetry uses Qualitative meter where syllables are usually categorized as being stressed or unstressed, rather than long or short as is the case in Quantitative meter of Greek and Roman poetry. In Qualitative meter, the combination of the iambic foot ᵕ ̷ and the trochaic foot ̷ ᵕ forms an Antipast foot. Book I, Verse 1 “Paradise Lost” by John Milton provides an example of the Antipast foot as shown below.

Labels:

Paradise Lost,

qualitative meter,

quantitative meter

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Choriamb Foot

Choriamb is a metron in Greek and Latin poetry consisting of four syllables in a pattern of long-short-short-long ¯ ˘ ˘ ¯ that is a trochee ¯ ˘ alternating with an iamb ˘ ¯. In English poetry, choriamb is sometimes used to describe four syllables which follow a pattern of stressed-unstressed-unstressed-stressed ̷ ˘ ˘ ̷ . In English poetry, the choriamb is often found in the first four syllables in standard iambic pentameter verses. The following verses 6, 9 and 10 found in stanza 2 of the Homostrophic ode written by John Keats’, “Ode to Autumn” provide examples as shown below:

According to prosody, it is not uncommon for poets to vary their Iambic Pentameter, while maintaining the iamb as the dominant foot. However, convention allows that these variations must always contain only five feet. The second foot is almost always an iamb. The first foot is the one most likely to change by the use of the inversion technique. This technique counteracts the metronomic effect by substituting for an iamb another type of foot whose stress is different. So it is not unusual to see any of these (trochee, spondee, dactyl, anapest or pyrrhic) appearing in Iambic Pentameter verses. The inversion mostly tends to fall on a trochee. Another common departure from the standard Iambic Pentameter is the addition of a final unstressed syllable which creates a feminine ending or what is referred to as a weak ending.

Homostrophic Ode consists of a number of stanzas alike in structure. The poet is free to decide on the structure of the basis stanza, with respect to the:-

- number of verses in the stanza

- verse length

- rhyme scheme

in accordance with the demands of the content.

-----

American spelling: meter, anapest

British spelling: metre, anapaest

According to prosody, it is not uncommon for poets to vary their Iambic Pentameter, while maintaining the iamb as the dominant foot. However, convention allows that these variations must always contain only five feet. The second foot is almost always an iamb. The first foot is the one most likely to change by the use of the inversion technique. This technique counteracts the metronomic effect by substituting for an iamb another type of foot whose stress is different. So it is not unusual to see any of these (trochee, spondee, dactyl, anapest or pyrrhic) appearing in Iambic Pentameter verses. The inversion mostly tends to fall on a trochee. Another common departure from the standard Iambic Pentameter is the addition of a final unstressed syllable which creates a feminine ending or what is referred to as a weak ending.

Homostrophic Ode consists of a number of stanzas alike in structure. The poet is free to decide on the structure of the basis stanza, with respect to the:-

- number of verses in the stanza

- verse length

- rhyme scheme

in accordance with the demands of the content.

-----

American spelling: meter, anapest

British spelling: metre, anapaest

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Is Barbados the Hurricane's sweetheart?

My Videos

Click on Videos to view

Bajan Voicing Latin Vowels

Bajan Voicing Classical Latin Alphabet

Bajan Voicing Short Vowels in Classical Latin

Bajan Voicing Long Vowel Sounds in Latin Words

Bajan Voicing Latin Diphthongs

Bajan Voicing Latin Vowels

Bajan Voicing Classical Latin Alphabet

Bajan Voicing Short Vowels in Classical Latin

Bajan Voicing Long Vowel Sounds in Latin Words

Bajan Voicing Latin Diphthongs

Haiti

Haiti Under Rubble from 7.0 Earthquake

Natural disasters whenever and wherever they occur impact on all of our lives. The Good Book says we are our brothers and sisters keepers lead by the Holy Spirit. Hence, we must do our part when disaster shows its ugly face. Any assistance, great or small, given from generous and loving hearts has equal weight. I'm passing on this information I received that Barbadians can go to First Caribbean Bank to donate to the Disaster Relief Fund for Haiti. The banking information is shown below:

First Caribbean Bank Account--2645374-- Cheques can be written to: HELP #2645374

For more information click on this link

My thoughts and prayers are with the people of Haiti.

First Caribbean Bank Account--2645374-- Cheques can be written to: HELP #2645374

For more information click on this link

My thoughts and prayers are with the people of Haiti.